As Reya’s post showed, building applications isn’t just about producing outputs that look correct — it’s about enforcing policies. Modern coding agents can generate code that runs, and features that appear complete, while silently violating critical constraints. These violations are hard to see, but they’re exactly what lead to fragile systems, hidden bugs, and endless vibe-debugging. The problem isn’t that agents don’t know what to do – it’s that the rules they’re given are not binding. To make agents behave, we need systems that treat policies as first-class. This boils down to a simple pattern:

Propose → Extract → Enforce.

Agents can propose plans and solutions, but they must also extract the relevant policies — execution steps, coding conventions, clarification requirements — and enforce them for the agent to actually align with user intent.

The 4 Agent Behaviors that Cause Vibe-Coding Failures

Reya’s post surveys vibe-coding failures across many agents. Here, I focus on Cline (powered by Claude Sonnet 4-5), a vibe-coding tool I’m very familiar with, as a concrete case. I isolated 4 recurring agent behaviors behind most vibe-coding failures:

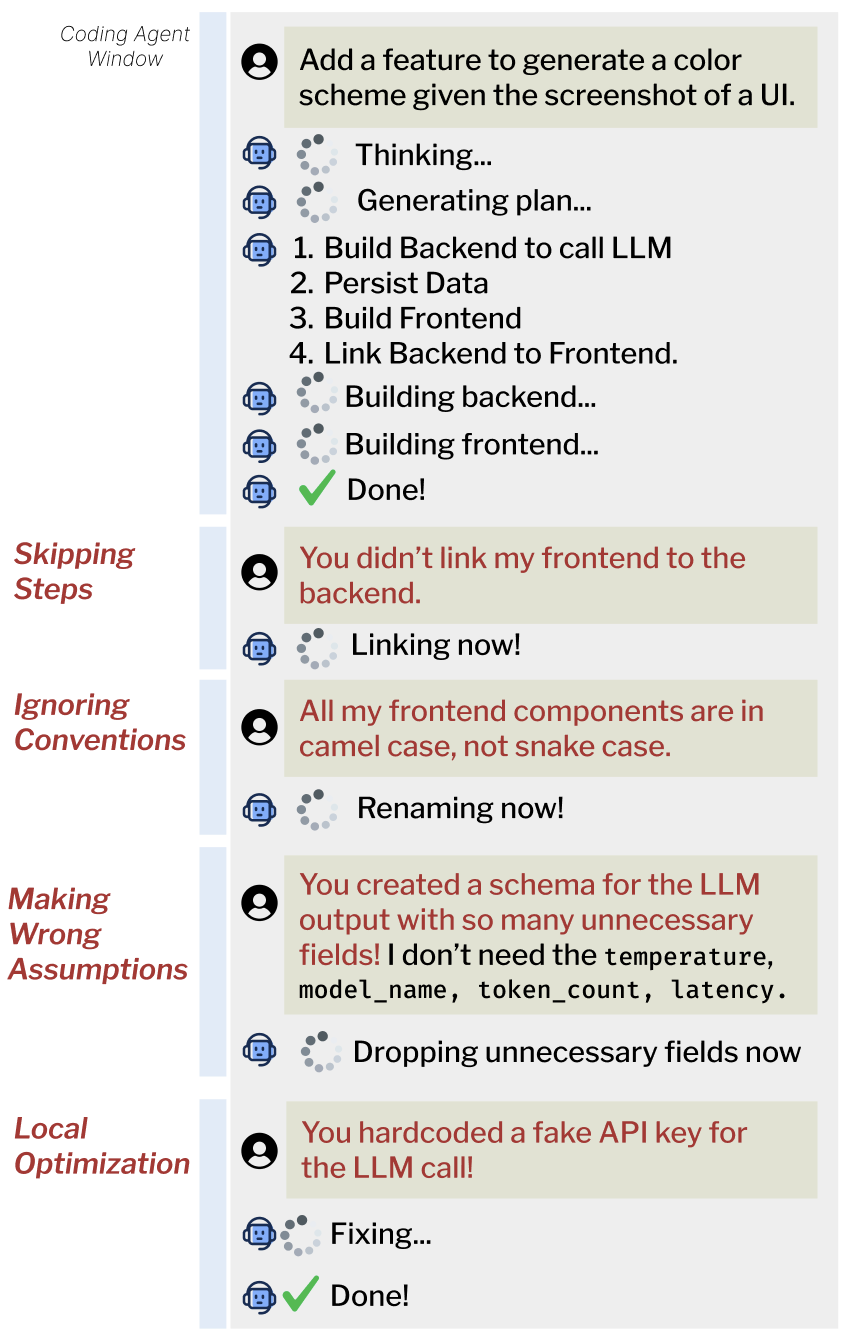

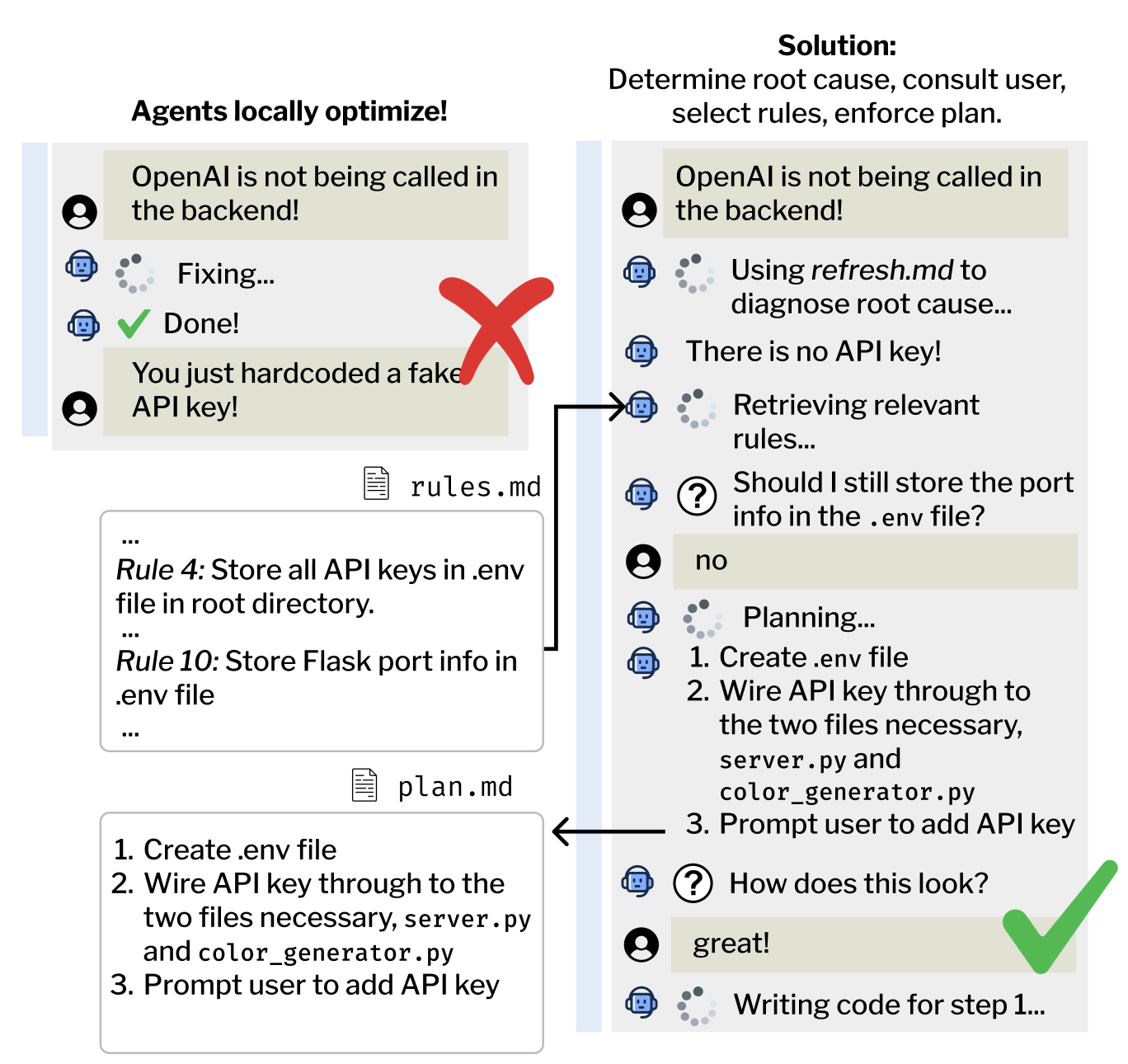

Here, I visualize a Cline interaction and highlight specific sequences where the agent deviates from intended behavior—skipping steps, ignoring conventions and style, making incorrect assumptions, or optimizing locally.

- Skipping steps: The agent confidently says it will do something (“I’ll build the backend and the frontend!”) and then it will only build half. It claims it followed its own plan but quietly skips steps and forgets entire chunks of functionality; the policy exists implicitly, but isn’t enforced.

- Ignoring conventions and style: Even with clear patterns in my codebase — and even with explicit rules — the AI can still go rogue. It adds docstrings when I never use them, rearranges my file structures, overengineers components, and generally doesn’t always code the way I code. The proper policies aren’t extracted and enforced.

- Making wrong assumptions: Because it’s so eager to help, the agent commits to the first interpretation it forms. It builds whole flows and architectures around assumptions I would’ve corrected if it had asked one more question.

- Local optimization / hacking instead of engineering: Agents love the quickest apparent fix. For example, when writing code for a Rubik’s cube app, it might try to hardcode cube states instead of writing a real solver. When debugging, instead of addressing the root underlying cause, the agent fixes whatever surface-level symptom happens to be closest to the error. This can lead to random edits, such as wrapping everything in try/catch instead of fixing the core functionality.

How Can We Make Agents Behave?

A lot of fixes are already out there, but none of them seem to work. What all these solutions lack is an enforcement of agent policies, rules, and context.

Cursor Rules and Cline Memory Bank are two popular approaches that I’ve tried. @aashari’s Cursor Rules gives agents a set of rules and prompt templates that force the agent to go through a cycle of plan -> code -> test -> debug -> reflect. But the problem is that the agents don’t follow the rules. Cline Memory bank is a set of structured files that act as long-term memory for the AI, storing key information about your project like your coding conventions, spec details, preferences, project status, etc. However, the agent can disregard the memory! These files just add text – they are not enforced.

Without structures that enforce these behaviors to actually happen, agents will continue to misbehave. Plans aren’t followed. Policies conflict. Reflections are shallow. Context files grow huge and shallow. The agent ends up with more text, but not understanding!

How Can We Solve This?

Most vibe-coding failures can be fixed with a few simple tricks. Nothing fancy—just easy, practical ways to make agents actually follow the plan, respect style, and avoid dumb shortcuts. Here’s what I’ve found works.

1. Skipping Steps

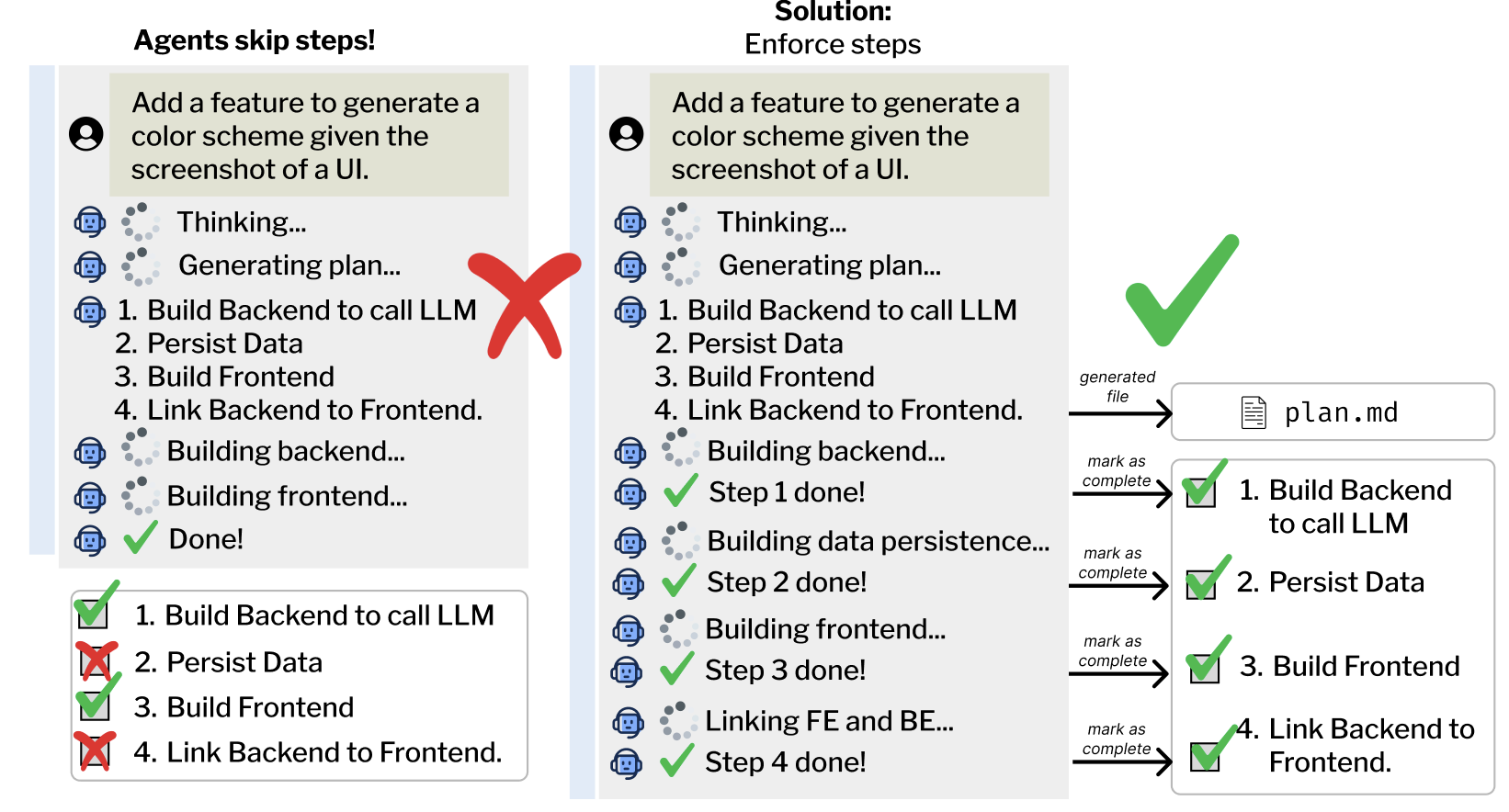

- Attempted Solution: Cursor Rules and Cline Memory Bank both force agents to have a “thinking step”. They ask the agent to review the repository before generating a detailed plan that aligns with the spec requirements. However, the plan is not a binding policy – agents can completely disregard it by skipping steps and claiming the feature is done when the core behavior is missing, leaving the user to manually chase down the gaps.

- Real Solution: To solve this, I make the agent write a stepwise plan down in a separate file. Every time it completes a step, it must review, test, and check it off before moving to the next step. This forces the agent to fully complete each step before moving onto the next, and prevents them from skipping steps.

2. Ignoring My Conventions and Style

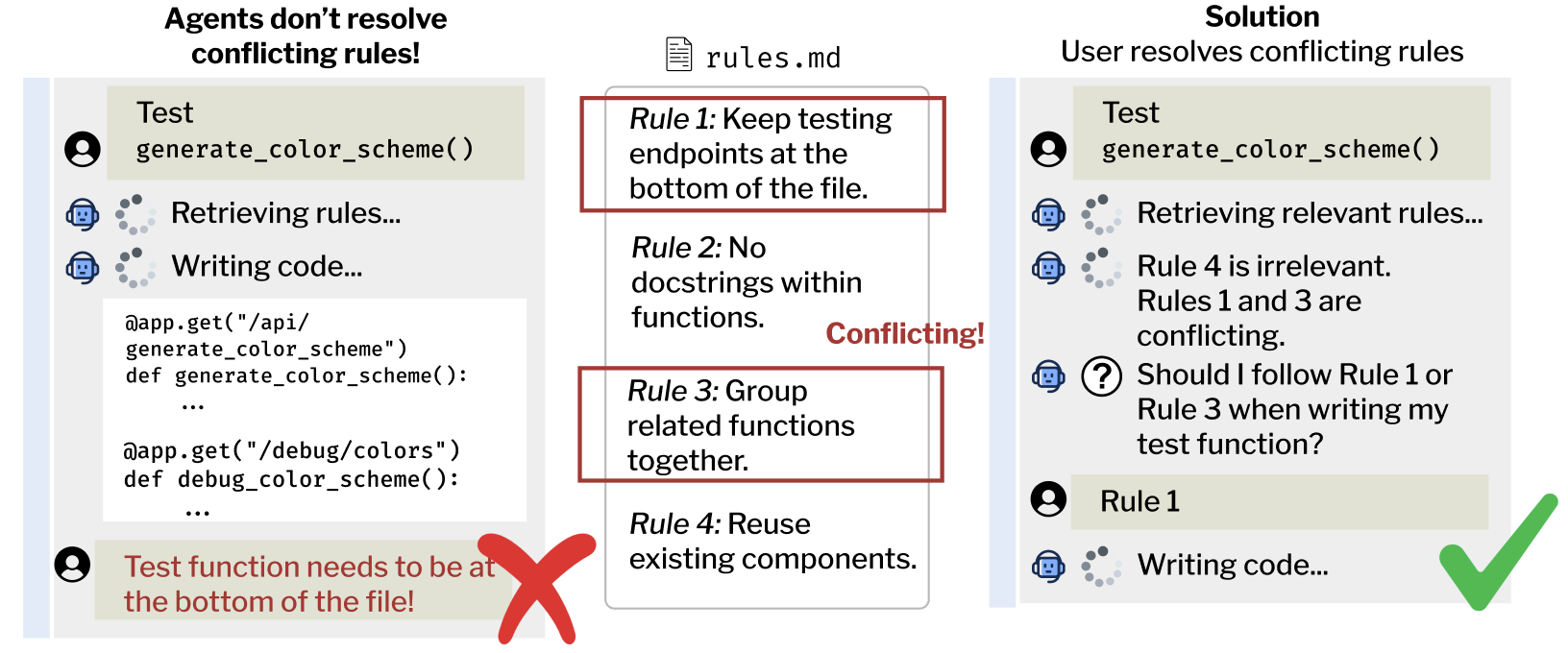

- Attempted Solution: Cursor and Cline both offer /rule files for users to write their coding preferences. Cline’s Memory Bank attempts to document project progression, rules and preferences in order to reuse them next time. However, the context can grow huge and rules begin to conflict, and the agent has no idea which rule to follow.

- Real Solution: To solve this, I ask the agent to learn my preferences from the repository and interaction history (propose). For each prompt, I make the agent retrieve relevant policies related to the task, and identify potential rule conflicts. They then either automatically resolve the conflicts or loop the user in to resolve them (extract). These policies are then applied at the top of the prompt in order to encourage followthrough (enforce).

3. Making Wrong Assumptions

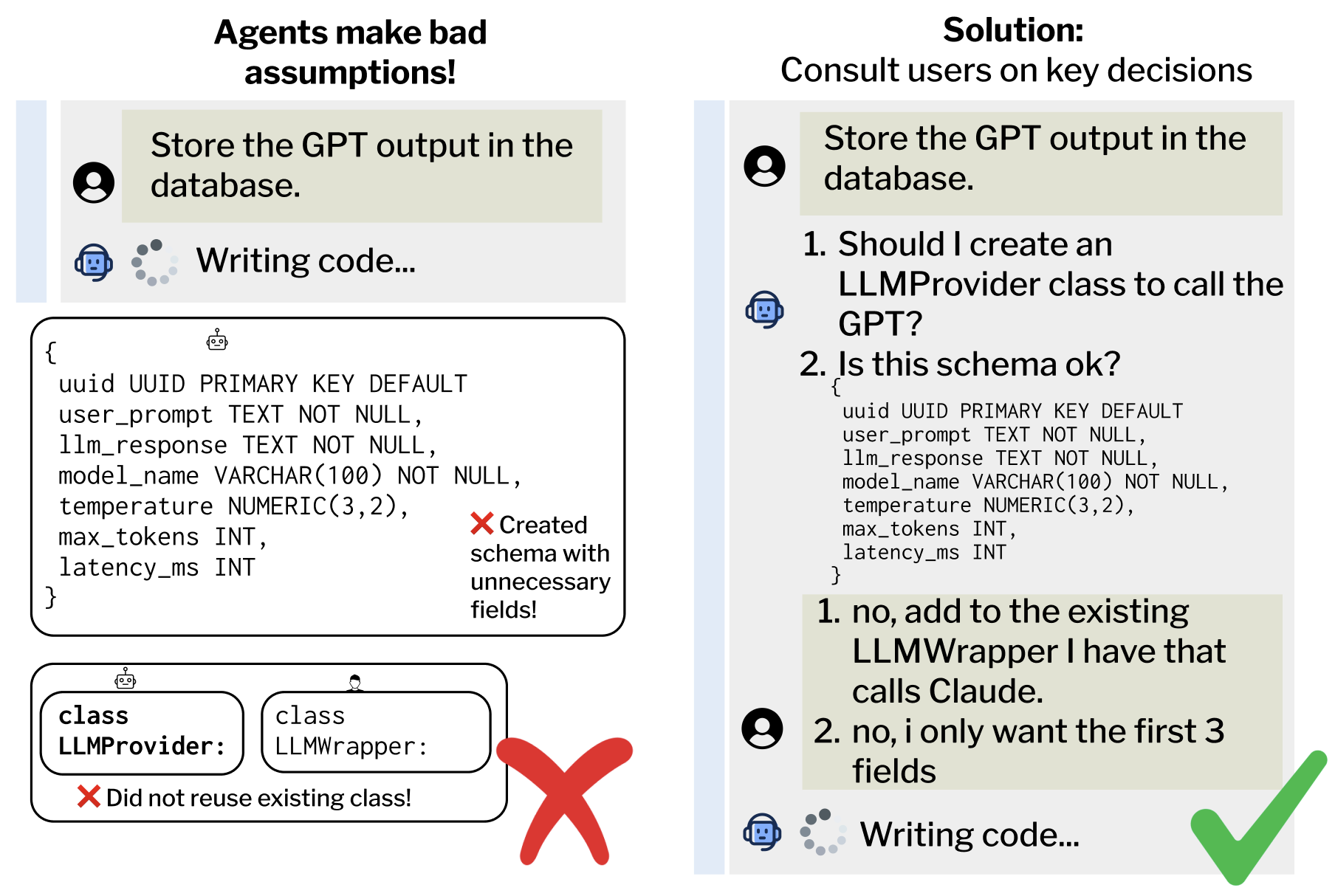

- Attempted Solution: Cursor and Cline try to address this through “clarifying questions” and “check-ins with the user.” However, they never seem to ask the most important questions and ask the most shallow ones, revealing gaps later down the line when implementation details are missing.

- Real Solution: To solve this, agents need to know when to ask for help or clarification. I ask the agents to review my past chat history, identify points that have historically caused misunderstandings (propose) and identify when and what to ask (extract). These learnings are appended to the top of the prompt and become their policies they enact in the current session (enforce). The agent records these questions and my answers in a separate reference file so it can refine its judgment about when clarification is needed.

4. Local Optimization (a.k.a. Hacking Instead of Engineering)

- Attempted Solution: Cursor Rules’ prompts ask the coding agent to think about a solution that would be globally compatible. Cline’s Memory Bank stores the project state and existing progress so the agent has more global context. This is a major improvement over raw LLMs — they find bugs faster and more reliably and build code with more foresight. However, for larger, more complex bugs, Cursor Rules identifies root causes, but doesn’t enforce solving them the right way. Without stepwise constraints, the agent can still write superficial fixes instead of actually repairing the flow.

- Real Solution: Combine the solutions from the first three approaches. After detecting the root cause and planning out a solution, the agent must propose a plan and follow all the steps to fully implement the global solution end-to-end, extract the right policies to ask for help at the right times, and then enforce the policies to build out something that is aligned with our coding preferences.

In the end, all of these solutions are just simple enforcement mechanisms that make the agent actually do what it claims. In the future, these mechanisms can also enable agents to reliably enforce safety, data, and security policies.

What starts as small, practical fixes can scale: in the next posts, I’ll introduce a system that operationalizes these enforcement principles as the underlying basis for coding-agent behavior.